His Secret of Success with Women: “When You Are Done Listening, Listen Some More”

Leonard Cohen, our greatest troubadour of the soul, has been an inspiration to me since my 1960’s childhood. That’s when my Aunt Esther gave me two albums: “Songs from a Room,” and “Songs of Leonard Cohen.”

During the mid 1950’s, Esther Cohen, Leonard’s older and only sibling, married Victor Cohen, a New Yorker who, coincidently, had the same last name. Victor was my mother’s older brother. Esther and Victor lived on New York’s Upper West Side and never had children. They were both colorful, brilliant people who travelled the world many times over.

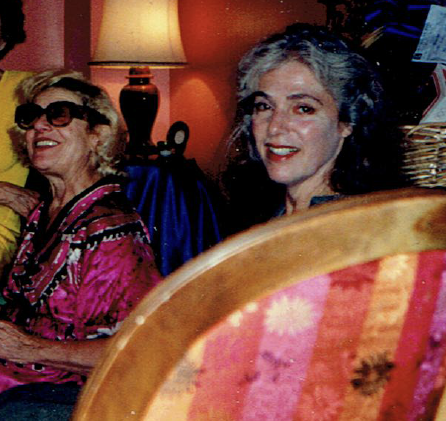

Esther loved talking to me about Leonard, and I loved listening to her. She was his greatest fan, which is saying a lot, given the cult-like adoration that many, especially in Europe, felt for him. Esther lived vicariously through his adventures and enormous international success.

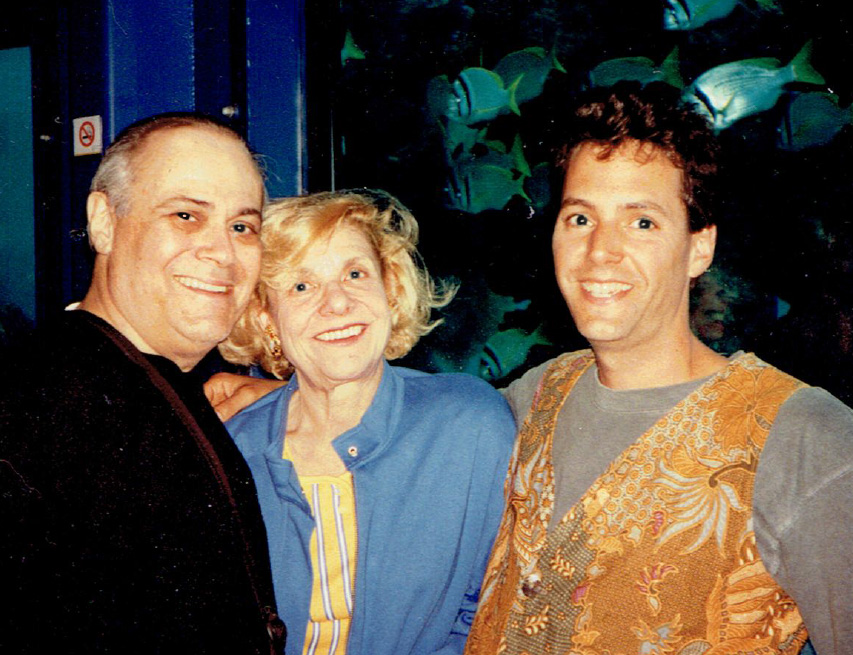

My uncle Victor, an eccentric small business owner, gave me my first job, in his tiny textile company in Jersey City, when I was 13. Throughout my life, they were the only uncle and aunt that I was close to. For more than 60 years, until Esther’s death two years ago, my mother and my aunt were the closest things to sisters that each of them had. I can think of few Jewish holidays or family events during the past half-century that my elegant, stylish Aunt Esther did not attend. Leonard did not have other nieces and nephews, so during the few years that his children, Adam and Lorca, lived in New York, they also joined our family events.

After I became an adult and Leonard a famous performer, Esther took me with her to some of the most memorable, soulful concerts I ever experienced. At Leonard’s July 6, 1988 Carnegie Hall concert for his “I’m Your Man” tour, I sat next to Aunt Esther and Uncle Victor in the great house seats she always received from her brother. Toward the end of the sold-out concert, Leonard asked his beloved sister and brother-in-law to stand and be acknowledged by the crowd for their decades of support. They stood up next to me as the spotlight shone on their faces and thousands of people applauded. Esther glowed. She never forgot that precious moment, and neither did I.

My mother, Jane Greer, died in January, 2018, about one year after Leonard passed away. She had been a New York artist since she was a Brooklyn teenager.

Jane probably first met Leonard at Victor and Esther Cohen’s small wedding in New York City on January 17, 1957. Victor was 30, Esther 27, Leonard 23, and Jane, soon to turn 21 and quite beautiful. Leonard was in his first (and only) year of graduate school, at Columbia University, living at the run-down Chelsea Hotel.

Jane began socializing with her brother’s new brother-in-law. She said that they liked going to Williamsburg to dance in the streets with the Hasids. She described him as a poet, a romantic and a bohemian. My mother was an art student at New York University at the time. Leonard was focused on poetry and writing, not music, and I imagine they enjoyed the 1950’s Beatnik scene, in the smoky Greenwich Village coffee houses and the Cedar Tavern, where Allen Ginsberg first read Howl.

In an unexpected candid moment, my mother once told me that she even once dated Leonard, for a very short while. She remembered him as charming, immodest, and irresistible to women. “Everyone wanted to sleep with Leonard,” she told me, knowingly.

Minutes after learning of Leonard’s death on November 7, 2006, I phoned my mother to inform her of it. “Oh, Leonard,” she gasped, then burst into tears.

During the fifties, Leonard, his sister Esther, and my mother, also socialized with Leonard’s sophisticated, gorgeous New York girlfriends, the photographer Susan Brockman and Leonard’s earliest serious lover, Anne Sherman. Although Anne and Leonard did not stay together for long, she remained a close friend of my mother for decades, as did Susan.

Leonard’s songs have had an enormous influence on me since I was 12 years old. He set my appetite for music with lyrics I could understand, lyrics that had deep meaning and soul-wrenching insight. Leonard Cohen was certainly not everyone’s cup of tea; people who had heard of him either adored or despised him. As I grew older, I was often pleasantly surprised that, coincidentally, my romantic partners shared a taste for his music. “Bird on the Wire” was the first song I learned to sing and play on the guitar. “Sisters of Mercy” and “Anthem” remain two of my favorite songs.

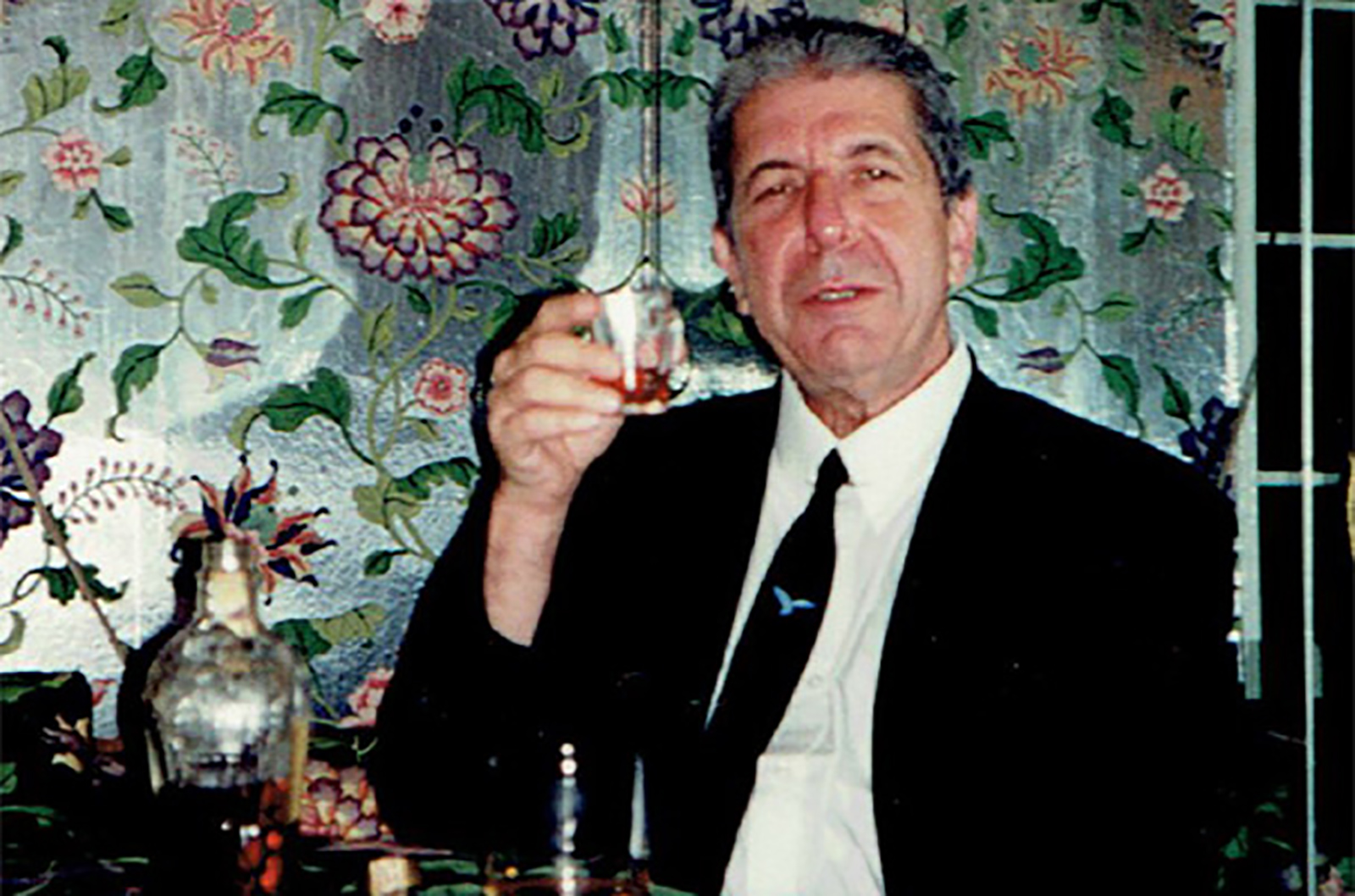

I rarely saw Leonard, but when we did meet, at Esther’s home in New York, backstage at a New York concert, at his home in Montreal, or later, in Los Angeles, he was completely present, attentive, intense, gracious and wise. His voice was as deep and penetrating in person as in his records.

Leonard was technically not my uncle, but my uncle-in-law, a term that does not exist in our culture. But we both came from very small families, and had few blood relatives. Leonard was, and remains, my influential spiritual uncle, a great teacher and source of poetic inspiration.

I will never forget Leonard responding to my frustration over troubling world events with calm, but far from calming words, “Don’t you know Jonathan: the killers are in control.”

When I think about politics, about injustice, about suffering, my analytical mind races for solutions. Since that day, half my lifetime ago, Leonard’s observation that “the killers are in control” remains with me, alongside his most lyrics, like a stop sign announcing: be aware of reality, no matter how challenging it may be. Work to be the change, yes. But act with acceptance. As Leonard sang in “Anthem,” “Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

Leonard believed that this life is not meant to be an easy ride, or a journey into perfection. Or that we can ever truly understand the experiences that others are here to experience. “We each live in our own private hell,” Leonard confided in me, during a brutally honest conversation.

And yet despite it all, as part of it all, I, and so many others, join Leonard in gratitude as I “stand before the Lord of Song with nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah!”

Leonard had a dark sense of humor. When I introduced him to a young Canadian doctor friend, he said, ‘Doctor, I have this problem. It’s called aging. Can you do something about it? If not, I am going to die.”

From his very first album, the 1967 ‘Songs of Leonard Cohen,” death has loomed large in Leonard’s vision. Yet it has always been accompanied by grace, by spirit, by rebirth. As Leonard wrote in “Sisters of Mercy” a half century ago, “If your life is a leaf that the seasons tear off and condemn, They will bind you with love that is graceful and green as a stem.”

Leonard was not one for small talk. As a teacher, he provided skillfully placed words of mentoring wisdom. Decades ago, during one of our visits together, I expounded to him my belief in the historical evolution of individual spirituality afforded to our generations by the relatively fewer time commitments, and relaxed societal restraints, of modern times. I suggested that we had more freedom to evolve spiritually than our ancestors in the shetels of the old country, because we did not have to conform to mundane jobs and strict patriarchal roles necessary for survival.

Leonard shook his head. “What do you know about their inner spiritual world?” he challenged. “A simple shoemaker could have been speaking to God every day of his life as he went about his work, or singing in the synagogue, or putting on tefillen. You have no idea what they were experiencing. People have had deep spiritual involvement with God throughout time.”

I once asked Leonard whether he had a regular spiritual practice. He said, “At night, before going to sleep, I reflect on the events of the day. I meditate on how little control that I actually had over any of it.”

Soon after that, in 2001, Leonard gave me this piece of unsolicited advice: “Go to Mumbai and see (the spiritual master) Ramesh Balsekar while he is still in the body. He is in his eighties, so you need to get there soon.”

I travelled to India, and, with Leonard’s introduction, was warly welcomed by Ramesh and his small community. I spent a week of daily satsang, asking questions and hearing wise, memorable answers from a living master.

Leonard’s advice for success with woman was even more helpful: “Listen well,” he admonished me, in his husky intense voice, as he shared glasses of whiskey and stared at me with focused intent. “Then listen some more.” I nodded my head and he looked at me during a long, contemplative pause. “And when you think you are done listening, listen some more.”

Leonard’s work, and his influence, have made me a better listener, a better writer, a better lover, and a better liver.

Like millions of others, I feel blessed to have been deeply touched by his music, words and raw soulfulness.

And even, for a number of memorable times during my adult life, to have been enriched by his illuminating wisdom.

As Leonard wrote near the end of his life, our bodies fall apart. And then we die.

But the songs, the poetry and the soul of Leonard Cohen will always be with me.

This article first appeared in the Huffington Post on November 11, 2016. It was revised, with additional photos, on January 5, 2026.

Related Posts

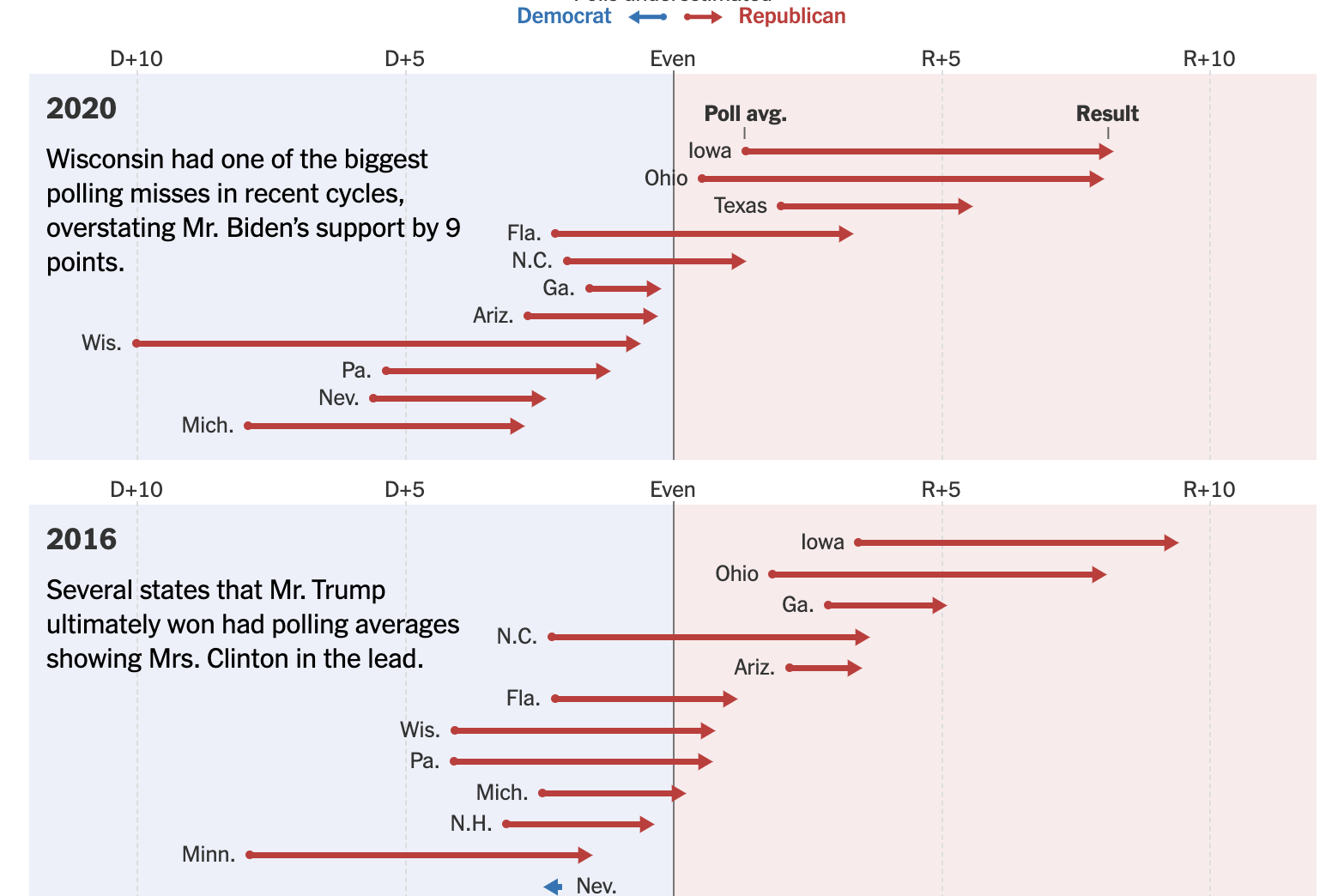

Washington Post Column Proves Biden Can’t Win

Just the other day I happened to wake up early. That is unusual for an…

Town & Country: Inside the Forbes 400 List

One of the easiest ways to improve travel photos is shooting in better light,…

EV Everywhere to build 5 MWh mobile battery charging station

One of the easiest ways to improve travel photos is shooting in better light,…