January 14, 2024 4 min to read

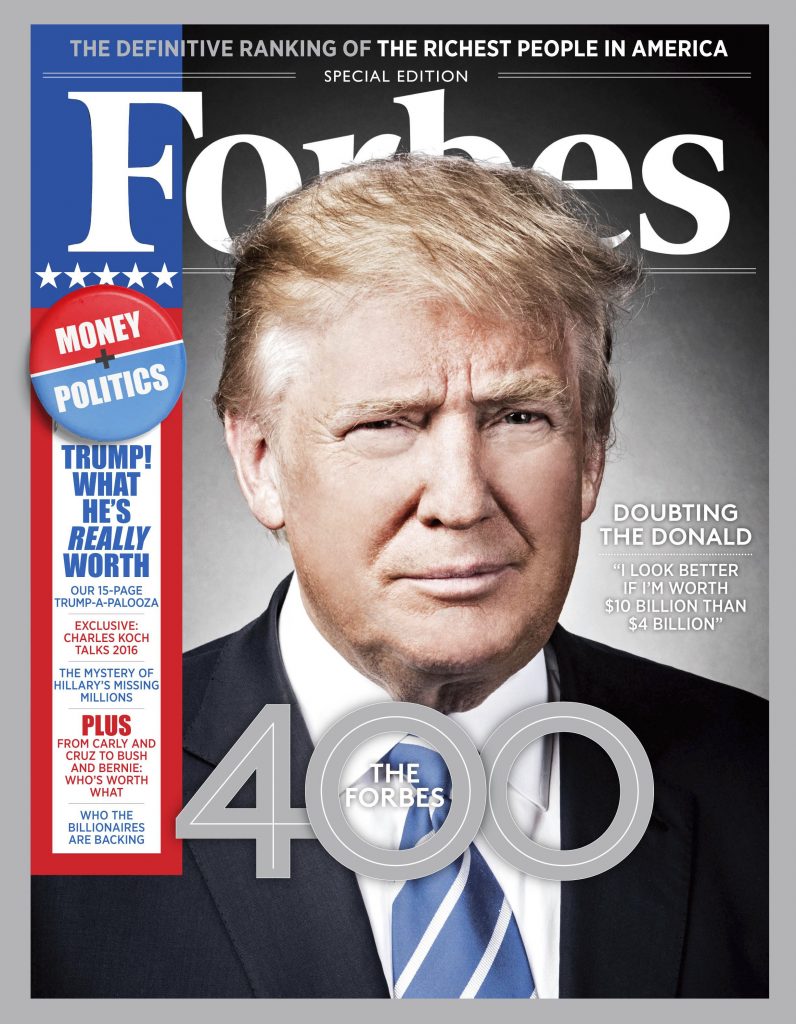

Town & Country: Inside the Forbes 400 List

Publication : Articles, Politics, Trump

This article first appeared in Town & Country here on January 15, 2019.

How to Get a Spot Among the Billionaires on the Forbes 400 List

Jockeying, backstabbing, fraud: How far will rich people go to be on—or stay off—the list.

“We have much better locations!” barked the future president of the United States. “We should be in the top category!”

It was June 1, 1982, and I was sitting in Donald Trump’s cavernous Fifth Avenue office interviewing the then CEO of the Trump Organization for Forbes magazine. I had just laid out my typewritten “prospect list,” a preliminary compilation of names of New York real estate tycoons who were candidates for the first Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans. At the top, Harry Helmsley was the only one with a net worth that might approach $1 billion.

A small group of highly respected families, like the Roses and LeFraks, who had built or bought much of Manhattan’s housing, were next, at $500 million. At the very bottom, with a question mark, was the Trump family, at $100 million for father Fred and Donald and his siblings combined. “There’s no contest between us and the other families,” Trump added, sounding like a resentful third-grader as he shook his head.

From that day, Trump began a years-long campaign to convince first me and then subsequent generations of Forbes reporters and editors that he was worth far more than any other real estate titan in New York. I would not realize the full scope of his efforts until much later. But at the time, Trump’s reaction offered the first inkling of how alluring the “rich list” formula would prove to be to competitive billionaires. It was also a harbinger of what reporters at Forbes, and now its many competitors, would come to expect in their dealings with the megarich.

The Forbes 400 was the brainchild of Malcolm Forbes, the energetic New York businessman who spent decades building Forbes magazine, which his father had founded in 1917, into one of the world’s most influential business publications. Despite his success, Malcolm envied the yearly Fortune 500, a competitor’s ranking of top businesses that had become a lucrative, internationally known franchise.

In 1981, Malcolm proposed to his editors an annual ranking of the wealthiest Americans—something that had not been attempted before. The name and number he chose for the list was an alliterative nod to “the 400,” a phrase that entered the lexicon in 1892 in reference to the number of guests who could fit into Mrs. Astor’s Fifth Avenue ballroom and who therefore represented the highest echelon of American society.

Research for the first list started small. Malcolm pulled me out of the reporter bullpen and turned me over to Shelly Zalaznick, the magazine’s formidable managing editor. Zalaznick, who died in 2012, promised that the magazine’s bureaus in Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC, would help with the research, and he set a three-month deadline. Equipped with a thick printout of the major shareholders of large companies, hundreds of recent SEC filings from the magazine’s library, and a listing of the 500 largest private companies in the U.S., I set out to identify the wealthiest Americans.

It was an impossible task. Forbes’s swamped bureau reporters could offer only token help to a 23-year-old greenhorn on what many regarded as a fool’s errand. My own research proceeded slowly, and when the deadline arrived I was not even close. Directing cigarette smoke rings at me across his desk (it was the ’80s), Zalaznick shook his head at the suggestion that completing the list would require more time, travel, and personnel. “I will tell Malcolm that you tried but it couldn’t be done,” he said.

Malcolm had other ideas. A few days later I was summoned to the large conference room on the second floor, where the top editors worked. The tone had shifted. A senior editor was assigned to lead a dedicated team of reporters. We were given a new deadline of one year.

Determining the net worth of those who owned large blocks of publicly traded companies was relatively easy, but the only way to learn which other Americans were worth at least $100 million (our cutoff in 1982) was through painstaking intelligence gathering. The staff fanned out across the country and visited dozens of cities to speak with wealthy people themselves, those who did business with them (including mortgage brokers and bankers), those who asked them for money, and those who wrote about them for local papers.

Read the rest of the story at the Town & Country online here.