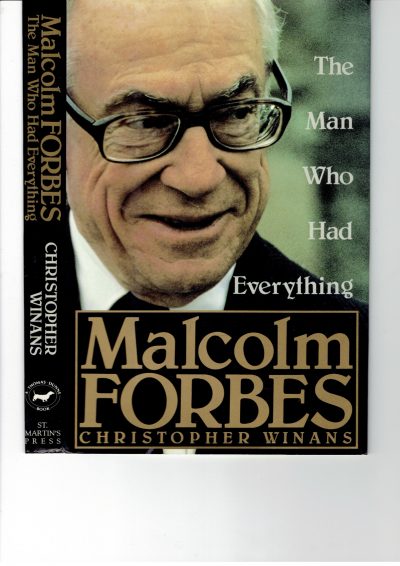

“Rich List” chapter excerpt from biography, ‘The Man Who Had Everything Malcom Forbes’ by Christopher Winans (PDF here).

Jonathan Greenberg who started at Forbes in 1980 as a research assistant, was asked in June 1981 if he would volunteer to work on a Rich List, as the project came to be known internally. From the beginning, it was clear this was Malcolm’s brainchild.

Malcolm had told Michaels, who hated the idea (“I was hung up on the risk, he on the opportunity,” Michaels would write later), to figure out how it could be done. Michaels kicked it over to Zalaznick, who also initially wasn’t thrilled. To begin with, no one believed it was possible to do such a list; that was the major criticism. It’s not like ranking publicly traded companies whose financial information is disclosed in accordance with federal Securities and Exchange Commission laws. Tax returns for private individuals arc proprietary. How could Forbes uncover the necessary information to confidently say such a list was authoritative?

Because Michaels viewed the project with such disdain, the staff generally saw any related assignment as punishment- certainly not a good sign for one’s career.

Michaels and Zalaznick could think of many obstacles that would make the job impossible, but they could not alter the most important fact of all: this was the boss’s idea. Greenberg was paired with assistant managing editor Jim Flanigan, now a Los Angeles Times business columnist, for a two-month stint to get started.

Greenberg’s initial function was to call the 500 biggest companies to determine who owned them. Meanwhile, the bureaus- Houston, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington- were told to accumulate local rich lists and related information and relay it all to Flanigan. Like Michaels and Zalaznick, the bureaus also perceived this as an odious, impossible job and thus did the bare minimum. The fact that everyone detected Michael’s lack of commitment to the project didn’t help.

“What they sent Flanigan amounted to nothing more than a few newspaper clippings,” Greenberg says. “Clearly this wasn’t a high priority.”

By mid-August, it was clear that the job was far from done. Zalaznick was convinced the job couldn’t be done. The next step was merely to go back to Malcolm with the proof that the idea was impractical. Says Greenberg, “We tried to do it and failed. This was the message that Michaels and Shelly then took back to Malcolm.”

Zalaznick had sent a memo to Malcolm telling him why he opposed the project. First, it would require a huge commitment of reporters’ time when the staff already was stretched to the limit. Second, Zalaznick didn’t believe there was a way the job of identifying the 400 richest Americans could be done accurately. Thus, once it came out, “there would be four hundred people in this country who would know with certainty that Forbes was full of shit,” Zalaznick says.

Malcolm responded quickly to both criticisms. First of all, he was willing to commit whatever resources would be necessary to get the job done. “I don’ t care what it takes; I want it done.” Second, Malcolm conceded that the first rich list might be riddled with inaccuracies, but experience would lead to improvements and greater reliability.

Zalaznick may not have been entirely convinced, but it wasn’t the kind of issue one puts one’s job on the line for. And the Rich List would go on to become an excellent training ground for reporters; it required a lot of travel, a lot of interviewing, and a lot of delving into public records to root out information that private citizens fight to keep secret.

For Malcolm, money was no object in getting the necessary resources to surmount the obstacles. Even time initially wasn’t important. Whatever it took, Malcolm was committed to the concept. He was convinced this was a hot idea.

“That embodied the nature of Malcolm’s leadership ability,” Greenberg says. “Very rarely did he pull rank in a way that has left such an impression on the magazine. It wasn’t just money.” It wasn’t just that this would be a great ad-sales vehicle. “It was fame. The Fortune 500 had always been such a barometer, and it clearly irked him that nobody quoted the Forbes 500.”

This was Malcolm’s answer. He knew he would be achieving what no one else had done on quite this scale. He wanted something that people would talk about the way they talk about the fortune 500 or the Dow Jones averages.

Now the effort got under way in earnest. The appointment of a senior editor, Harry Seneker, to work on the project full time put the effort on a higher level of importance. A number of publications that had done local rich lists- Texas Monthly, Minneapolis magazine, New Jersey Monthly, Philadelphia magazine – were studied for ideas about how to gather and assess information.

The entire effort caused something of a split in the editorial office: between people pulled away to work on Malcolm’s new project and everyone else lined up behind Michaels in the belief that Forbes ultimately would be embarrassed by the effort.

Michaels, for example, clearly wasn’t pleased when it was decided to assign Greenberg to the project for an entire year. Greenberg, for his part, felt caught in the middle. The project fascinated him, but “if Michaels doesn’t like something that Malcolm wants to do, being assigned to it automatically puts you on Michaels’s shit list,” Greenberg says. (Still, Michaels ultimately would heap praise on Greenberg when he left the magazine in August 1983 with an editorial note headlined A BEAUTIFUL SWAN SONG(PDF), a reference to Greenberg’s final story.)

By spring 1982, Seneker’s Rich List crew had grown to include a host of talented reporters- including John Dorfman, who later went on to write for the Wall Street Journal, and Jay Gissen, later a founding editor of Manhattan, inc. The strategy was to send reporters to spend a week in each of several major cities. Greenberg alone went to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Denver, Minneapolis, Chicago, Cleveland, Columbus, Pittsburg, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Miami, and Tulsa. Jay Gissen concentrated on the Oil Patch.

Gissen, one of the few who didn’t view the assignment as a booby prize, volunteered for it. He was fascinated by the prospect of developing a snapshot of personal wealth in America. Who had it? Where did they come from? How did they earn it? In the beginning no one had any idea how much money it would take for inclusion among the 400 richest Americans. Would the cut off be $10 million, $100 million, more? It became readily apparent early on that it took about $10 million just to have the visible trappings of great wealth- a private jet, a tremendous house, expensive cars, frequent appearances at luxurious resorts.

The instructions were to keep the purpose of the digging a secret. The fear was that someone might try to stop the process with a lawsuit charging invasion of privacy. Many of the targets weren’t public figures. In fact “reclusive” is probably the most commonly used adjective with the words “millionaire” and ” billionaire.” Forrest E. Mars of the Mars, Inc. candy company in Hackettstown, New Jersey, was a perfect example; worth billions of dollars, he’d done everything he could to avoid the kind of publicity that definitely would flow from the Rich List.

A man like Mars may spend his life trying to avoid the spotlight, but as the owner of a major corporation, he can’t hide his wealth completely. But what about truly hidden wealth? How do you track down the very discreet rich? This turned out not to be too hard. It was easy to go into a particular town and find out through the local newspapers who had the most amount of financial clout. But nailing clown precise figures wasn’t so easy. A number of factors had to be considered, not the least of which was an individual’s debt load. “We’d go in to a city,” Gissen says, “and talk to the local newspaper’s business editor. We’d talk to local bankers in confidence. Most wouldn’t tell us anything, but some would.”

The Forbes researchers found that wealth generally came in the form of company stock, oil and gas holdings, real estate, media properties, and inheritance, which included all of the above. Soon, Forbes reporters with expertise and sources in these various areas began to contribute valuable information. Greenberg, for example, became particularly interested in the enormous value of Manhattan real estate. About 10 percent of the original 400 were on the list because of New York real estate holdings.

“Granted, a list like this has to be based on a pile of absurd assumptions,” says Gissen, later editor of the Cable Guide. “The value of stock and oil in the ground, for example, isn’t real until you sell it.”

While debt was perhaps the biggest unknown factor, the hidden role of silent partners also clouded the picture. Nevertheless, it became apparent that the cutoff for inclusion on the first list was going to be about $100 million.

Maintaining secrecy about the project would be no easy task. Forbes reporters were talking to local-newspaper business editors, society columnists, fund-raisers, politicians, and the semirich. Making such inquiries without tipping one’s hand about one’s purpose isn’t easy. A newspaper in Columbus, Ohio, ran a story in the winter of 1981 reporting that Forbes had come to town in search of candidates for a list of America’s richest. Ultimately, it did no harm.

Meanwhile, roughly eighty people threatened to sue Forbes if they appeared on a Rich List. The main fear among potential subjects was that the Internal Revenue Service would scrutinize the list for income not listed on returns. An IRS agent in the New York office, however, once told Gissen the agency had taken a look at the list but didn’t see anything worth investigating.

Also, there was protest over Malcolm’s insistence that the list include names of nonadult children, which was perceived as a sort of potential shopping list for kidnappers and terrorists. In fact, Gissen and Greenberg both implored Malcolm not to include children’s names, but Malcolm insisted they be included (perhaps he saw the value of establishing a data base of rich heirs).

An equally important reason for secrecy was to keep the news from leaking out to archrival Fortune for as long as possible. Presumably, since Fortune had done a similar list -of private companies and who owned them- it was conceivable that it could develop a competing rich list on relatively short notice and steal Malcolm’s thunder.

One area full of reclusives was the field of New York real estate investment. Greenberg spent the last three months of his research on it, managing to identify and rank the big players. The sources turned out to be less impenetrable than he expected. To begin with, he had the advantage of relatives close to the business. A grandfather was an accountant to many of the biggest New York real estate investors of the 1930s and 1940s, and that helped open doors to some of the heirs of these investors. And his brother in the real estate business in New York helped him identify the major individuals in Manhattan ‘s biggest land deals.

But the most useful sources were the subjects themselves. While they were reluctant to discuss their own holdings, they talked freely about everyone else’s. Usually they were accurate. Everyone seemed well informed about who owned what. By playing one against the other, Greenberg was able to nail down a fairly accurate accounting. Many candidates for the list tried different tactics to avoid inclusion. William Randolph Hearst, Jr., of the publishing fortune, for example, tried to convince Malcolm to keep his name off the list. Hearst had a legitimate reason for fearing public attention to his wealth; even without a published rundown of it, the Symbionese Liberation Army correctly determined how much it could expect the Hearsts to be able to put their hands on in an attempt to get back his kidnapped niece, Patricia. Still, Malcolm wouldn’t be moved. “Tell you what, Bill,” Malcolm told him. “You shut down Town and Country magazine and I’ll cancel the Rich List.”

One day a real estate baron came into Seneker’s office, obviously agitated about the prospect of getting on the rich list.

“Harry immediately called me in,” Greenberg recalls. “He didn’t want to spend one second alone with this guy. He was very nervous.” Greenberg walked in. The man was just standing there sweating profusely. “I want to talk to Harry Seneker,” he said. Seneker refused to ask Greenberg to leave them alone. “Can we close the door?” Again, Seneker refused. He said he wanted off the list. He said he wasn’t worth it. Besides, he was embroiled with relatives in a dispute over his assets. Having them detailed in Forbes could hurt. He kept looking at Seneker and Greenberg. He didn’t have anything further to say. After a long, uncomfortable silence, he said, “Don’t you think you could do something here?” It was apparent the visitor was willing to do almost anything -perhaps even pay- to avoid the publicity. He was shown the door. At one point there was even a rumor that someone was selling people on the promise that for the right amount of money, he could get your name off the list. A host of petty bribes were offered by individuals wanting off-from free football tickets to barrels of pop corn to, in one case, $50,000 for two reporters.

Several Rich List candidates who wanted off made powerful arguments, appealing to the reporters’ personal morality. How would you feel if you’d worked hard all your life to amass a fortune and keep it secure? The prospect of gaining wide publicity for it might threaten that security.

“People said, ‘It’s on your head,'” Greenberg says. “It was hard, particularly when you felt they were entitled to their privacy.”

But once you were on the list, a new set of concerns arose. One secretive New York developer who made the first list, much to his displeasure, came back as the second annual list was being compiled and told Greenberg, “You put me on this list. If you take me off, it’ll make me look bad. I got no choice but to stay on this fucking list.”

The process of ranking the other real estate tycoons in New York was helped by Greenberg’s practice of sitting down with each subject with a preliminary list in front of him. The subject wanted to see who stood where. Greenberg’s list had thirty or forty names paired with the addresses of the properties they held, what they paid for them, what their liabilities were, and who their partners were. It was all on one page.

“They were fascinated to see how they were placed,” Greenberg says. “For all of them, this was probably the first time they’d ever seen such a list. And they all wanted to move themselves up on the list or at least push others down. They were extremely competitive. As a result, you’d learn everything about everyone else. They’d say, ‘So-and-so doesn’t own that all by himself’ and proceed to tell you who the other partners were. Then there were the people you never heard of, but they’d tell you about them because they envied their holdings.”

Part of what made this process of eliciting information work so well was Greenberg’s refusal to tell anyone else what others said about them. That way, a subject could feel more comfortable about being a source.

Donald Trump was one of those who insisted he was worth more than Forbes thought. In interviews with Greenberg, he aggressively deconstructed the wealth of everyone above him. He wanted to be on top.