February 24, 2018 6 min to read

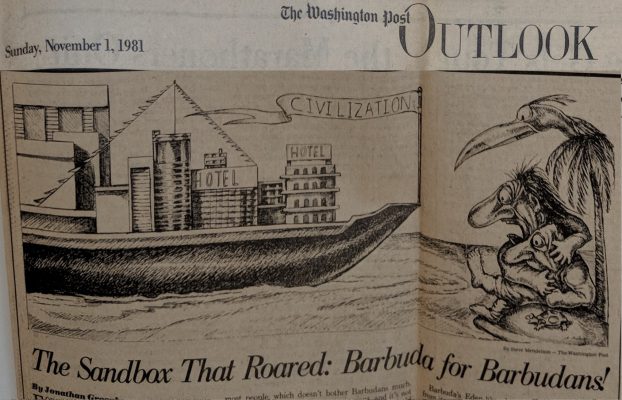

The Sandbox that Roared: Barbuda for Barbudans!

Publication : Articles, Uncategorized

Forget Afghanistan or El Salvador. The real takeover threat these days is in Barbuda.

Okay, you never heard of the place. Neither have most people, which doesn’t bother Barbudans much. Barbuda is no industrial or strategic giant, and it’s not part of the Third World. It’s more like an Other World nation a tiny Caribbean paradise whose chief exports are sand and stamps, whose wealthiest inhabitant may be the grocery store operator, whose goats, horses, cows and sheep outnumber its citizens, and whose people worry about a takeover by the so-called “civilized world.”

Barbuda’s Eden-like character stems in good part from its common ownership of almost all of the island’s 62 square miles of land. That means no mortgage payments or rental costs natives just plant plots where they please and no class conflict to speak of. everyone has rights to land, there’s little difference in power among Barbudans,” says anthropologist Riva Berleant Schiller, who has lived there.

Poverty is no problem. “There’s no hunger in Barbuda,” says Hilborne Frank, chairman of the Barbuda Council. “If a man is hungry and a fisherman has fish, he will give the man some.” Gwen Bucci, an American who recently returned from a visit to Barbuda, adds: “They’re a very healthy and proud people. Nobody looks hungry, and though there’s no dentist, they all seem to have teeth.”

Mostly the 1,200 islanders two-thirds of whom are children- relax on unspoiled beaches, look for lobster among coral reefs, hunt wild boar at will or watch an incoming plane.

Five months of the year the plane brings in the island’s few vacationers, who shell out $290 a person nightly to stay at Barbuda’s only hotel, the 30-room Coco Point. But there’s no Club Med, no hippie holdouts, not even an obscure voodoo cult. Stamp collectors, who will buy nearly $1 million of Barbudan philatelic specials this year, are among the only foreigners who have even heard of the island.

That’s how Barbudans would like matters to stay. But the outside world -in this case the nearby resort island of Antigua, aided by Britain may not be capable of leaving a good thing alone.

In granting Antigua its independence, effective today, Britain decided that the most appropriate future for Barbuda would be to incorporate it into its tourist-happy neighbor a notion Barbudans have been struggling against.

Barbudans don’t struggle with tanks (there are no gas stations on the island) or with guns (the place is also devoid of violent crime). They simply plead with Britain.

But evidently Britain no longer appreciates the importance of keeping Barbuda under its benign thumb. “We’re not in the business of being colonialists anymore,” says Stanley Arthur, high commissioner of Barbados and Britain’s leading representative in the West Indies.

That’s all very well for old imperialists to say, but it’s not very satisfying to Barbuda, which since 1976 has been a semi-autonomous dependency of Antigua, with its own elected council and a representative in the Antiguan parliament.

It’s not merely that Barbudans don’t especially like Antiguans, which they don’t. Diann Beazer, a 23-year-oldwho completed her secondary school education on Antigua, says other students often picked fights with her because she was a Barbudan. “It’s not hidden. You can feel the antagonism between the two people,” she remarks.

“Antiguans treat us like third-class citizens,” says Barbuda Council chairman Frank. “Under the Antiguan constitution we would become like slaves to them.”

Barbudans remember, for example, Antigua’s support for the 1977 “Poo-Poo Project” before the Barbuda Council. Under that proposal, a northeastern U.S. company would have brought in tanks of human excrement, spread it over parts of the island to dry, and returned it to the United States as fertilizer. One local lawyer explained to a group of concerned islanders: “An American company is going to transport all the poo-poo released by all the high-class, well-fed white people in Boston.”

The U.S. company was to spend $7.5 million to build a deep-water harbor at Barbuda and to provide jobs for the islanders, who would have bagged the dried dung. The locals adamantly opposed the plan, yelling, “Are we no American poo-poo: YA!”

Barbudans preferred to stick to selling stamps and $25,000 a month of their top-quality fine sand, which is how much the nearby islands of Guadeloupe, St. Croix and Martinique need to mix with their rougher volcanic sand to make cement.

Another product Barbudans want to leave in the outside world is marijuana. Eric Burton, the grocery store owner who is Barbuda’s representative in the Antiguan parliament, says he is scared the Antiguans will allow Rastafarians from Jamaica to return to the island to plant the weed. A few months ago Burton got the police to rid Barbuda of the “Rastas” when they tried to “seed the island.”

But chiefly the Barbudans worry that tourist-happy Antigua will destroy their paradise by allowing ownership and development of land. They have visions of Antigu run casinos and of organized crime being attracted to their peaceful island.

Grocer Burton, who claims that Antiguans have already begun chopping wood to clear sites, says, “We want the Antiguans to have nothing to do with our land.” Adds anthropologist Berleant-Schiller: “Antiguan-style tourism would definitely destroy the Barbuda way of life.”

It should have suprised nobody, then, when an overwhelming majority of Barbudans recently elected council-men who stood for independence from Antigua. Lloyd Jacobs, who today becomes Antigua’s first ambassador to the Uníted Nations, says, “Historically the people of the two islands have lived together as one. This ‘independence’ is just the whim of a few people who would set themselves up as king and duke.” But his view is not shared by many Barbudans.

Jacobs insists that his larger, more powerful island of 70,000 has helped tiny Barbuda over the years. Antigua collects import duties and sells Barbudan stamps in return for providing its dependent neighbor with 12 school teachers, some civil servants, two nurses and 15 policemen (viewed by Barbudans as an occupying force).

A fully independent Barbuda appears far-fetched, especially since the majority of the island’s inhabitants are children. Nevertheless, the Barbudan Council today will recognize their island as an independent nation, even if nobody else does.

The Barbudans have prepared a declaration for the occasion, signed by nearly every one of the island’s 400 adults. It states: “We will establish a lawful separate territory founded on liberty, based tolerance

on and respect for internationally recognized human rights and concerned to further the quality of life.”

They have been encouraged by the success of the tiny island of Anguilla in gaining de facto independence not long ago, In1969, Britain announced plans to grant St Kitts independence and control over Anguilla, whose 6,000 people then revolted. It was an embarrassing, though bloodless, affair, a comic opera of sorts. A few hundred English paratroops, marines and policemen had to be dropped on the island to end the uprising, but in the end the British gave in.

If this doesn’t work for Barbuda, perhaps it could persuade a couple of Sandinistas from Nicaragua to spend some time catching fish on the island. That might scare the Reagan administration enough to take Barbuda under its wing and rescue it from any outsiders.

This article was first published in the Washington Post November 1, 1981) to see original pdf click here.